On the afternoon of July 6, 1862, Curtis’s army came to an abrupt halt on Clarendon Road northwest of Hill’s Plantation where fallen trees in front of James’s Ferry blocked their advance. Curtis had taken his army on a forced march through a tempest wasteland infested with the enemy. He was not just short on supplies and isolated in enemy country, but had cut himself lose from his line of communication. He risked getting bogged down and possibly surrounded, which could have had disastrous results for his already hungry and weary army.

In June Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman issued Order No. 17 calling for irregular militia units to be formed in order to swarm the invaders and drive them out. As a result the White River region was infested with bushwhackers and guerrillas. If Curtis could be delayed long enough there, Hindman might be able concentrate his forces and hit the Federals while they were in a vulnerable position. To do so, he ordered Gen. Albert Rust and his force of about 5,000 men to move as rapidly as possible to Cache River and halt the Federals there. Locals were called upon to spoil water wells with animal carcasses, block roadways with fallen trees, and harass the Federals as much as possible. “Hold the line at Cache River,” Hindman ordered, and Curtis’s army would disintegrate from want of supplies in a matter of days. Continue reading ]]>

BY CHRISTOPHER WEHNER

The last week of June 1862 found Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’s Army of the Southwest in serious trouble. Reinforcements he had requested failed to materialize. His supply line was over 300 miles long from Rolla to Batesville, rendering it untenable. His men were on half-rations and his meager cavalry force was breaking down from a lack of forage. Having scratched his plan to take Little Rock, Curtis concentrated his army, cut lose from his supply line, and headed down the White River in eastern Arkansas in hopes of reaching Helena and fresh supplies.

On the afternoon of July 6, 1862, Curtis’s army came to an abrupt halt on Clarendon Road northwest of Hill’s Plantation where fallen trees in front of James’s Ferry blocked their advance. Curtis had taken his army on a forced march through a tempest wasteland infested with the enemy. He was not just short on supplies and isolated in enemy country, but had cut himself lose from his line of communication. He risked getting bogged down and possibly surrounded, which could have had disastrous results for his already hungry and weary army.

In June Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman issued Order No. 17 calling for irregular militia units to be formed in order to swarm the invaders and drive them out. As a result the White River region was infested with bushwhackers and guerrillas. If Curtis could be delayed long enough there, Hindman might be able concentrate his forces and hit the Federals while they were in a vulnerable position. To do so, he ordered Gen. Albert Rust and his force of about 5,000 men to move as rapidly as possible to Cache River and halt the Federals there. Locals were called upon to spoil water wells with animal carcasses, block roadways with fallen trees, and harass the Federals as much as possible. “Hold the line at Cache River,” Hindman ordered, and Curtis’s army would disintegrate from want of supplies in a matter of days.[1]

Sometimes desperate Federals soldiers wandered carelessly from camp in search of food, only to be captured, tortured and sometimes killed by bushwhackers. Comrades discovered their mangled bodies tied to trees riddled with bullets. The Army of the Southwest attempted foraging but the land was barren. “Women and children are houseless,” wrote a soldier with the Second Wisconsin Cavalry, “with little to eat or wear.” There was nothing for “man or brute in the country passed over by my army,” noted Curtis.[2]

At James’s Ferry the Cache River was a swampy bayou choked by cypress trees making it impossible to circumvent the obstacle of fallen trees. Curtis’s army would have to cut its way through the barricade. It was late in the afternoon and the path not yet cleared, forcing Curtis to camp along the road for the night and in the morning send out pioneers to the other side to finish the job.

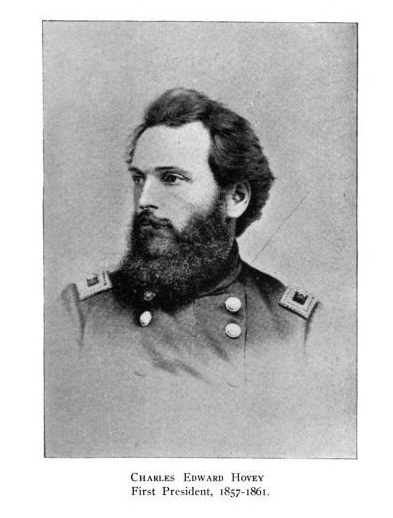

The next morning Col. Charles E. Hovey (Second Brigade commander and Colonel of the 33rd Illinois) was ordered by Brig. Gen. Frederick Steele (whose division was at the front) to cross the Cache River, secure a defensive perimeter, and clear the surrounding woods of “guerrillas.” Steele’s instructions gave no indication for how far they were to push out in their sweep.[3]

About 6:00 a.m. Hovey took the pioneers, four companies of the 11th Wisconsin, four companies of the 33rd Illinois, and a contingent of 1st Indiana Cavalry with a small steel gun to the other side of the river. The pioneers immediately began to clear the debris on the eastern side of James’s Ferry. While Hovey oversaw the work he sent Col. Charles L. Harris of the 11th Wisconsin down Clarendon Road towards Cotton Plant in reconnaissance with most of the men. Before noon Colonel Harris and elements of the 11th Wisconsin encountered advanced guards from William H. Parson’s Texas Rangers near Hill’s Plantation. Thirty minutes to an hour later, at least a full regiment of Confederate cavalry converged in force and nearly overtook Harris and his seriously outnumbered reconnaissance party.[4]

The above events are about the only conclusive and fairly indisputable ones of the battle at Cache River. Beyond them lie nothing but conflicting or missing reports, and confusion. One of the main reasons for the disparity is the absence of a Confederate report. We have individual remembrances from surviving soldiers, but no report from Gen. Rust who commanded the Confederate forces. On the Federal side there are several reports, but the two most important ones by Hovey and Lieu. Col. William F. Wood (1st Indiana Cavalry) are in conflict. Colonel Harris of the 11th Wisconsin was wounded and did not file a report, or no report survived.

By and large battle summaries for Bayou Cache go as follows:

Union Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis moved on Helena, Arkansas, in search of supplies to replace those that had been promised but never delivered by the Navy. The Confederates under Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman attempted to prevent this change of supply base by continually skirmishing with the Union troops. The Confederates made a stand at the Cache River on July 7, 1862. As Union Col. C.L. Harris moved forward with elements of the 11th Wisconsin, 33rd Illinois, and the 1st Indiana Cavalry, moved forward, he blundered into an ambuscade. [My emphasis] The fighting became more general, and the Confederates, with a frontal attack, forced the Union to retreat about a quarter of a mile. The next Confederate attack, however, was stopped. With reinforcements, the Federals pursued the retreating Confederates and turned the retreat into a rout as the day progressed. [5]

The highlighted section points out the focus this paper. There are only two significant articles written about the battle. The first, appearing in 1989 by Glenn T. Nelson and John D. Squier, “The Confederate Defense of Northeast Arkansas and the Battle of Cotton Plant, Arkansas, July 7, 1862,” Woodruff County (Ark.) Historical Society publication, Rivers & Roads & Points in Between. The other is by historian William L. Shea, “The Confederate Defeat at Cache River,” which appeared in The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, summer of 1993. Though useful, Nelson and Squier’s article focused almost solely on the events of the day from a Confederate standpoint. Shea’s investigation sought to bring everything together. However, Shea essentially followed the battle narrative of the 33rd Illinois and as a result does a serious injustice to the 11th Wisconsin and 1st Indiana Cavalry.

* * * * *

Lets first review the events of the day from the perspective of the 33rd Illinois, a viewpoint that today dominates the battle description. The main sources used by Shea and other historians are Hovey’s official report, a St. Louis Democrat article by a correspondent name “Fayel,”[6] and Isaac H. Elliott and Virgil G. Way’s History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War, (1902).

Pursuant to orders, Hovey instructed Harris to take parts of eight companies (less than 400 men) and the canon in reconnaissance down Clarendon Road towards the town of Cotton Plant, about 6 miles to the southeast. After about four miles Harris’s skirmishers encountered a small group of Confederate cavalry at Hill’s Plantation at the junction of two roads: one heading southeast to Cotton Plant and the other southwest to Des Arc. According to Hovey, Harris then continued a “short distance” down the southeast road when he, having left James’s Ferry some time before, overcame Harris and ordered him to “hasten down the Des Arc road, and, if possible, rescue a prisoner just captured.” Hovey kept at least one company with him and sent Harris on his way.[7] This required Harris to turn his column around and hustle back to the fork and continue southwest towards Des Arc. There, according to Fayel and Hovey, Harris and his men passed a cornfield on their left and woods on their right and at a turn in the road they “fell into an ambush” at the end of a clearing.[8]

Fayel stated, “Texan regiments of cavalry…[were] drawn up on their right ready to receive them.” Being severely outnumbered, and taking a heavy fire, Harris’s men withdrew and the result was a retreat that was “temporarily… [in] panic.” During this time the canon, now under the command of the 33rd Illinois, and positioned along the road, became threatened during the frantic retreat of the 11th Wisconsin. However, the gun was saved by the heroic acts of the Illinois soldiers led by a Captain L.H. Potter.[9]

Elliott and Way in their History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War described the events without mentioning any hasty retreat. “The Wisconsin men at once savagely opened the fight, but the enemy swarmed upon them from everywhere and they were forced slowly back.” What is also interesting, yet ignored by historians, is that Elliott and Way make no mention of an ambush.[10]

In Hovey’s official report he stated that after a charge by the Texas Rangers the retreating men of the 11th Wisconsin “fell into some little confusion.” [11] He noted his arrival on the scene was shortly after this event. But he does not mention how much time had transpired since the opening volleys of the fight or how many charges by the cavalry had taken place.

At some point Hovey took command as Harris was wounded and “though fainting, fought.” A heavy fire from the 33rd Illinois greeted another charge by the Rangers and the result found the field littered with Confederate bodies. Hovey then ordered the men back to the cornfield where a fence rail would provide some cover. Hovey next discovered that the enemy was trying to get to his rear, but his men countered. There was another attempt to turn his left flank, but that was saved by one of his 33rd Illinois companies.[12]

Interestingly, Elliott and Way mention several charges, “again and again” by the Rangers before Hovey’s arrival. “Our troops had been forced back to the corner of the [corn] field where most of the 33rd had taken shelter behind the rail fence,” they documented, “About this time Col Hovey joined us and greatly restored the confidence of the troops…” According to Elliott and Way the retreat happened before Hovey was even on the field, yet Hovey takes the credit.[13]

Hovey did note, “No men could behave more handsomely than did the Eleventh Wisconsin on my right.” Yet he offers no detail or description, no justification. However, almost nothing in his report noted any of the activity on his right, except when presumably the 11th Wisconsin in their hasty retreat luckily thwarted an enveloping movement by a column of Rangers trying to cut them off from Clarendon Road.[14] Thus suggesting that they did something only by accident. The reason for Hovey’s lack of information concerning his right was because Harris was in command there. The size of the battlefield was potentially hundreds of yards in length.[15] In finishing up his report Hovey states:

I heard a shout in the rear, and before fully comprehending what it meant Lieutenant-Colonel Wood, of the First Indiana Cavalry, with one battalion and two more steel guns, came cantering up. It was the work of a moment for Lieutenant Baker to unlimber his pieces and get in position. The woods were now alive with shot and shell. The retreat became a rout. Our cavalry, led by Major Clendenning, charged vigorously, and the day was ours.[16]

On the surface, it appears the evidence is strong. Case closed. The 11th Wisconsin, in their haste to execute Hovey’s order to rescue captured comrades, blundered into an ambush. Their panic stricken retreat nearly cost them the battle. Hovey and his Illinois troops saved the day. Hovey was in charge of the expedition, he was present for a significant amount of the fighting, his report is accurate, and Fayel was an unbiased observer. Hovey was later recommended for promotion within the year to the rank of general for his performance at the Battle of Bayou Cache. It should be noted that historian William L. Shea largely supports Hovey and Fayel’s battle description.

However, three problems arise: 1) Hovey was not there for perhaps as much as the first 20 minutes of the fight; 2) his accounts were contested by both Col. Wood and members of the 11th Wisconsin; and finally, 3) as for Fayel, he was not present during the battle. His entire report was based on interviews.

In his St. Louis Democrat report, Fayel followed the same narrative as Hovey’s official report, but with a little more detail. His article closely followed the events taking place on Hovey’s left where the 33rd Illinois was positioned. Suggesting that his primary interview subjects were members of the 33rd Illinois. However, Fayel did mention some details Hovey left out, which brings us to the 1st Indiana Cavalry and their side of the story.

In his official report Wood’s description of his arrival mirrors that of Fayel, both contradicting Hovey (quoted above), Fayel wrote:

The arrival of this reinforcement [Col. Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry] proved extremely opportune. Col Hovey was posted about 150 yards from Col. Hill’s house, on the Des Arc road, and the army were not in view.[17]

This is an interesting comment, as according to Fayel, Hovey was not with his men at this point. After about an hour of fighting Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry appeared and were enthusiastically welcomed by Hovey and his beleaguered group of fighters. “There comes Col. Wood,” said Hovey, “we are all right now, boys.” Wood approached Hovey who instructed his cavalry to “pitch into ‘em,” and with that they were off towards the Rangers. By this time both sides were spent. The Confederates could be heard in the distance, but it was not know what they were doing. The Indiana cavalry rushed them and after about 20 minutes of fighting sent the remaining Confederates fleeing from the field. It was truly a rout at this point. Meanwhile, exhausted Federal infantry prayed that the charging was over. Both sides were battered and the field was littered with the dead and dying. “Bowels and brains were scattered on the ground,” wrote Fayel when he observed the battlefield hours later, “and the blood besmeared the bushes in the vicinity.”[18]

But Hovey makes little mention of Wood’s efforts and even downplays his involvement, stating simply, “Our cavalry, led by Major Clendenning [not even mentioning Wood], charged vigorously, and the day was ours.” Col. Wood stated in his report that when he arrived the infantry near Hovey were “standing in groups” near the woods. That Hovey was at this time “150 yards from Hill’s house” and not personally engaged in the fighting. When he approached Hovey, who seemed panicked, he was instructed to “pitch into them.” This Wood did as Fayel noted. Clendenning was a member of the 1st Indiana Cavalry and was later instructed by Wood to lead a critical charge that helped send the Confederates fleeing from the field in utter disorder. Wood contended that the Rangers were on their way back for yet another charge when he encountered them.[19] Hovey denied this and also denied ordering Wood to attack (he declared that the battle was essentially over), and accused Wood of making a reckless charge that only served to “sacrifice life unnecessarily.”[20]

The men of the 11th Wisconsin in correspondences and letters home repeatedly praised Col. Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry. They described Wood and his cavalry as “gallant” and arriving “just in time.”[21] One soldier of the 11th Wisconsin recalled that just before the arrival of the cavalry the “Rangers had the advantage. If they had charged [once more] at this juncture, they could have cut our small force to pieces.”[22] Other 11th Wisconsin reports deny that the situation was dire. What we have to remember is the physical effort displayed by all of the Federal troops during this battle. The days leading up to the fight consisted of exhausting marches. The men were on half-rations, some less, and with only putrid water to be found causing some soldiers to expire on a daily basis from sickness, fatigue and exposure. Confederate Gen. Hindman ordered a scorched earth policy as Curtis’s Army of the Southwest desperately and cautiously moved toward Clarendon and the hope of fresh supplies. Even before the battle started, Curtis’s infantry was in a weakened state. The two hours of fighting, along with the day’s march, must have rendered the men near exhaustion by the time Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry arrived. They had little fight left in them.

Just days after the battle the officers of the 11th Wisconsin wrote home to the Governor of Wisconsin and briefly described the events. In it they reported that the “entire command of Col. Hovey seemed in imminent danger” until the Indiana Cavalry arrived and charged the enemy, resulting in the scattering of the rebels and at that point the “work was done.”[23]

Wood wanted a court of inquiry to be formed as Hovey continued to contest and underscore the exploits of his men, however, both Steele and Curtis denied it. It should be noted that the 1st Indiana lost only one man killed and 9 wounded during the supposed reckless charge. In refusing Wood’s request, Gen. Curtis stated later, “colonel [Hovey], so far as relates to the order of Colonel Wood does great injustice to superiors as well as himself.”[24]

* * * * *

This leads us to the narrative of the day’s events as remembered by members of the 11th Wisconsin. I have purposely only focused on the major events that are in question, and will now go into more depth using primarily the documents left behind by the Badger troops.

Harris trusted Company D[25] the most. Known as the Richland County “Ploughboys,” they were made up entirely of wheat farmers and pioneers. Their charismatic and dashing Capt. Jesse S. Miller led them. Throughout his campaigns Harris consistently placed the fearsome Ploughboys in the advance as guards or skirmishers. On this day he did no different. As Company D approached the fork in the road near Hill’s Plantation they encountered six unknown cavalry soldiers[26] who they immediately fired on and dispersed. Though they failed to unhorse a man, they did shoot a “heavy shotgun out of the hands of one of them.” [27] They continued on to the fork, made a brief stop where the men drank from a fresh well and some cooked a quick breakfast at Hill’s house (no doubt confiscating items to eat). Based on the conditions of their prior marching, it seems reasonable that they would stop for a moment. They then continued down the southeast road towards Cotton Plant, but before doing so Harris ordered the “reconnoitering [of] the woods [that surrounded the road] for some distance around.”[28]

After proceeding about a mile Harris halted his column. “Officers consulted and we started [back] in the direction of camp,” wrote a soldier who was with Harris. About this time, Hovey, having just left Hill’s house, “came dashing down the road at full speed” and informed Harris that “the secesh had come up to the house and taken two of our boys prisoner.” Hovey in his official report documented this event. [29]

Hovey’s order is a very important aspect of this battle. Historian William L. Shea downplayed it suggesting that Hovey would not have given such an instruction. Instead, Shea surmised that Hovey called for Harris to “turn back and drive the rebels away from the army’s line of advance.” Which suggests that Harris and the 11th Wisconsin were not heading the right direction. Shea also reported that, “none of the Wisconsin soldiers mentioned such an incident.” Which is incorrect (noted above) as there were two men captured by the Texans and in need of rescue.[30]

* * * * *

“Two of our orderly sergeants were captured by the Rebels,” wrote Henry Twining after the battle. The Rebels had “lash[ed] them to a tree” and executed them with a “savage barbarity,” he wrote. Both bodies were riddled with bullets, one with 13 and the other sixteen. In another incident, a soldier from the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry was captured and dragged into the woods where the enemy reportedly “cut off his nose, gashed his check, and then cut his throat in three places.” Miraculously, he managed to get away and survived.[31]

Incidents such as these certainly would have made Hovey sensitive to the treatment Federal soldiers received once captured. By his own instruction, Hovey sent his entire reconnaissance party hastily down an unknown road, surrounded by cypress woods and swamps, in an area crawling with enemy cavalry and even more worrisome, bushwhackers. In his report Hovey admitted to telling Harris to “hasten” down the Des Arc Road. Harris was every bit the obedient soldier and would have executed this order without question. Though Hovey clearly had good intentions, his order is questionable, yet thus far historians have ignored this.[32]

* * * * *

Harris “immediately detached” Company I, led by Lieut. Chesebro, “around the woods” behind Hill’s house, “with instructions to follow the road running south” in hopes of intercepting the bushwhackers. This is an important instruction by Harris that historians have missed. This would allow Chesebro and company to observe the advanced guard of cavalry moving up Des Arc Road. (See map.) Meanwhile, Harris moved out with the rest of the main column. He returned to Hill’s house and continued down the southwest road. Hovey does not tell us what he is doing or where he goes while Harris heads down Des Arc Road. When Chesebro arrived near the cornfield, where it bordered the woods, “the enemy was seen coming north” up the Des Arc Road.[33]

As Company I approached the road, “rebel cavalry could be seen in front and on our right and left in the brush.” Harris sent Company’s D and I forward as skirmishers to disperse the enemy. Company I spread out across the road and along the cornfield at the southwest corner, just behind Company D; Harris and his adjutant (David Lincoln) road on horseback between the skirmishers and the main column. Along with them were six men from the 1st Indiana Cavalry manning the small steel gun commanded by Lieut. C. A. Denneman. At this time a quick exchange of gunfire sent the Confederates reeling back after suffering casualties.[34]

A young Texas farmer, David Carey Nance, was with the leading elements of William H. Parson’s Texas Rangers who the 11th Wisconsin just ran into. According to Nance, an advanced skirmish guard, the closest support was another guard of about 50 cavalrymen several hundred yards behind them. Nance and about twenty other men were surprised to run into the Wisconsin skirmishers (Company D) and as a result suffered casualties. Nance himself was hit several times by extremely accurate fire and miraculously managed to survive—he was later captured, but managed to escape. There was an initial clash and then the two groups drifted apart. Nance makes no note of an ambush in waiting for the Eleventh. They were just as surprised as the Federals.[35]

Scouts galloped back to inform the 12th Texas Cavalry, about a half-mile away, that their advance guard had encountered the enemy. With this information they were on the move towards the field. Behind them were the 17th and then the 16th Texas Cavalry, along with some Arkansas infantry; all were now in haste to the battlefield.[36]

Harris reformed his line, leaving the two companies of the 33rd Illinois back in reserve, and pushed on another couple hundred yards to the bend in the road. Contrary to Shea, who wrote that the canon was placed back off the road, Harris kept the small steel canon and its Indiana crew with him positioned in back of and between Companies D and I, who were staggered off the road on the right and left. This was a mistake and nearly resulted in the capture of the canon. Harris should have held the gun back with the main force as Shea presumed.[37]

As they approach the bend in the road they were met by a “volley” of fire that injured several men. Shea wrote that “a number of Wisconsin soldiers were killed” during this initial volley. The 11th Wisconsin suffered 44 casualties during the battle; eight of them fatalities, but reports from their members deny that anyone was killed during the initial volley. Fayel wrote that “five of our men” were killed and that Harris was wounded. Surgeon Henry P. Strong of the 11th Wisconsin, who was positioned just behind Harris, contradicted this stating, “I am quite certain that none [of the men] were killed until some time later.”[38]

The initial volley was most likely the 50-member advanced guard combined with the survivors of the advanced skirmish line. The terrain was not easy for cavalry to maneuver in and it seems unlikely that in a matter of minutes the 12th Texas Cavalry could have dashed to the front and deployed in full force in an ambush without being detected. As Shea noted in his article, the battle was a “meeting engagement” and not an ambush. The 60 or so Rangers poured significant fire into the skirmishers of the 11th Wisconsin and probably wounded many. But their fire was ineffective as they lacked proper weapons. Most of the Texans were armed with only what they brought from home; some with squirrel rifles and single barrel shotguns. Even with such poor weapons, had there been 1000 or so cavalry waiting in an ambush, as Hovey claimed in his official report, the unsuspecting 11th Wisconsin would have been decimated despite the “poor quality of Confederate arms and the cover provided by the dense woods.” It would have been more than the reported dozen or so wounded and killed in this opening salvo.[39]

The woods indeed came “alive” as buckshot sprayed everywhere. It would have been immediately obvious to Harris and his men that they had encountered more than a half-dozen scouts. Several of his men were injured. Harris ordered the men down and the canon to fire away, “but it was not sufficient.” Still the firing continued. Companies G and H moved forward to join the others in a skirmish line. With the additional men and superior firepower they held their ground as “each man in the advance fired from five to twenty rounds,” reported a witness. In order to fire twenty rounds, they would have needed a minimum of 10 minutes, or an average of 2 shots per minute.[40] Fire from all around them quickly began to intensify as more and more of Parson’s 12th Texas Cavalry flowed in. At some point, suspecting that they were now out-numbered, Harris ordered his men to fasten bayonets, which later prove to be a wise decision.[41]

Surgeon Strong was soon busy attending to the wounded. He glanced up and saw “Col Harris and Adjutant Lincoln” on horseback directing the men and firing their revolvers. At this time a wounded Ranger was brought to him and revealed that elements of two Texas cavalry regiments were quickly filling the surrounding woods.[42]

A soldier in Company D noted that, “we soon found about 1200 coming on us all mounted.” From out of the woods charged Parson’s 12th Cavalry, “shouting like a thousand devils.” It was here that Company’s D and I, in the main path, suffered most of the casualties. Though out-numbered the extended skirmish line “repulsed [Strong’s emphasis] at the point of the bayonet” the charge. The dense forest was now filled with smoke and crackling gunfire. The 1st Indiana crew protecting the canon was decimated, four out of its six crew wounded. At this point, having taken heavy casualties and fearing they were going to be overrun, Captain Harris ordered his men to fall back. They were more than ready to comply and the result was a “temporarily panic.” As the frightened men began to run, the entire line retreated hastily. Harris, still on his horse and not wounded, turned his horse around and overtook the fleeing men, where he “ordered a halt.” He called out to his men, “Don’t never show your faces again if you run.” Calling on their honor the men rallied and an orderly retreat was commenced as the Rangers pressed them. Within moments of restoring order Harris was wounded in three places as the Texans perhaps charged again, this time forcing the men of the 11th Wisconsin back even faster.[43]

The 33rd Illinois was not standing idly bye for the 10-20 minutes since the opening shots. Capt. Potter and at least one company, hearing the opening shots, moved out and “joined their Wisconsin comrades,” who were moving back under the pressure of mounted and dismounted cavalry. “The little field piece…was ripping canister into the advancing column,” but still they were forced back. At about this point the 1st Indiana crew and its steel canon were in dire shape. Seeing that they required help, Potter and his company aided Lieut. Denneman and his battered unit, even staving off a Confederate attempt to capture the gun.[44]

Hovey neither was idle, but he was also not present during those opening minutes of fighting. Elliott and Way in their regimental history of the 33rd Illinois mentioned several charges taking place before Hovey reached the field. It’s hard to imagine what it would have been like to be there amongst the horrific confusion. Likely one charge became two in the memories of some, or two become one. So what charge did Hovey witness as he arrived on the field is ultimately unknown.

We do know from 11th Wisconsin correspondences that Mrs. Hill was home and that Federal troops searched the grounds and confiscated numerous items. It was also mentioned by one soldier that some Negroes had tipped Hovey of the two captured Federal soldiers that resulted in his order for Harris to hasten down the road. It would not have taken Hovey 20 minutes to cover a half-mile. So the issue is when did he first become aware of the firing? Hovey could have been in the house speaking with Mrs. Hill and simply did not hear the opening gunfire until the canon started.[45]

Hovey probably reached the field at the end of a second charge that sent everyone in flight including the 33rd Illinois troops. Hovey witnessed it from a distance as he arrived. Surgeon Strong, who was now well behind the action, mentioned “a moment’s conversation with him [Hovey]” as he reached the ground. James N. Butler was a member of Company E in the 33rd Illinois and was positioned at the edge of the woods near the road with the other Illinois companies. Behind them was the cornfield contained by a wooded fence. He describes the retreat during the second cavalry charge, “We were not in the thickest of the fight, but we were in the thickest of the run,” he recalled. As the 11th Wisconsin retreated in haste, the 33rd Illinois did so as well. Men fled down the road, some crawled over the fence and into the corn field, “the pursuing cavalry seemed to be moving at a snail’s pace in comparison,” he wrote. How far the men fled is not clear, but most likely not far. “Some of us wouldn’t have stopped until we crossed the Arkansas line,” he continued, “if it had not been for Col Hovey.” Hovey was probably still at Hill’s house when he heard the frantic retreat and crackling gunfire echo through the woods along the road. He quickly gathered up the 33rd Illinois men with him at the house, mounted his horse, and dashed down the road to the cornfield, which was no more than half a mile away.[46]

Hovey reported seeing Capt. Potter severely wounded while trying to help with the gun. The charging Rangers forced him and his men off the gun. But they rallied, aided by Lieut. Denneman who was never far from his post, and retook it before the Texans could haul it away. At this point Hovey took command of his men and ordered the canon to the rear. As Harris and Hovey frantically reformed their line, one company of the 33rd Illinois commanded by Capt. Isaac H. Elloitt (who would eventually become a general) repositioned itself on an angle off the cornfield and in excellent position to receive the Rangers as they charged. According to Strong, it was Elloitt and his company that played a key role in resisting the second charge while Harris regrouped his men. Hovey most likely ordered them to position.[47]

There can be no question that as Hovey arrived the situation was in a state of panic. As the 11th Wisconsin frantically re-organized, Hovey sent one Wisconsin company (it’s unknown which one) back with the canon to Hill’s house. The assault that Hovey witnessed as he arrived was estimated to contain “between 1500 and 2,000” Rangers according to Private McCarthy of Company D who was wounded during the fight. Hovey joined his men in repulsing the attack; even taking a bullet to the chest that luckily did not seriously injure him. Shea contends that after arriving on the field “Hovey relieved the reeling Harris and sent him to the rear for medical attention,” which does not appear to be the case as several members of the 11th Wisconsin mentioned Harris’ presence on the field until the battle’s end. Also, Shea offers no supporting evidence for his claim, whereas surgeon Strong noted Harris was involved in the fight up to the end and made no mention of him leaving the action.[48]

At this point, until the arrival of Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry, Hovey’s report stands alone. Surgeon Strong of the 11th Wisconsin was busy with the wounded, McCarthy was one of them, and the other correspondents and reports were either secondhand or unconfirmed witnesses.

After a third possibly fourth charge, Hovey was forced to take defensive actions to avoid being flanked. The Rangers again sent a column around the field in an effort to cut the small reconnaissance party off from its communications and support. This was thwarted by Hovey’s order that sent a company of the 11th Wisconsin back to Hill’s house, which might have been mistaken as reinforcements and sent the Texans back from where they came.[49]

Hovey next reorganized his line and reported actually advancing upon the enemy, which Surgeon Strong supports stating in his correspondence, “[Hovey] advanced down the road….” Shortly after this time Wood and the 1st Indiana arrived.[50]

When Hovey arrived on the field he immediately sent messengers back to James’s Ferry requesting support. While on their way back they ran into Col. Wood, who dashed off towards the fighting. Gen. Steel received the message about 30 minutes later, took immediate action, and sent up reinforcements.[51]

The Battle at Bayou Cache was a complete Federal victory. The deciding factors involved: superior firepower, a little luck, and most importantly superior leadership on the field in the form of Harris and Hovey, as well as other officers. They fought heroically and their men followed their example.

Did Harris “blunder” into an ambush? There is enough evidence to cast doubt on such a description. If there was culpability, it would lie with Hovey’s order that sent Harris hastily down Des Arc Road in pursuit of captured comrades. An honorable order, but placing his entire command at risk for one or two men was irresponsible, costly, and nearly disastrous. Harris and the 11th Wisconsin and the 1st Indiana Cavalry should be commended and given more respect than the official records, and unfortunately historians, have given them.

[1] The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies (Washington, D.C.: United States War Department, 1886) Series 1, Vol. 13, 36-37, 835 (cited hereafter as ORA).

[2] Correspondence to Janesville Daily Gazette, July 30, 1862; Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: August 9, 1862 correspondence from St. Louis; ORA, 363 – 364.

[3] Ibid., 141

[4] Curtis wrote in his journal that it was around 10 a.m. that the booming of canon was heard. (Shea, 147). Members of the 11th Wisconsin report various times ranging from 10 a.m. to noon as the start time of the battle.

[5] Online source: http://www.cr.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/ar003.htm

[6] William Fayel was a Civil War journalist who accompanied the Army of the Southwest in Arkansas. See footnote at the bottom of page 140, The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LII, No. II, Summer 1993.

[7] It has been generally accepted that Hovey kept one of the 11th Wisconsin companies with him at Hill’s house. Members of the 11th Wisconsin always contended that Hovey kept one of the 33rd Illinois with him, which makes more sense.

[8] ORA, 143.

[9] St. Louis Democrat, July 17, 1962.

[10] Isaac H. Elliott and Virgil G. Way, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War (Gibson City, Ill.: Gibson Courier Press, 1902), 28.

[11] ORA, 143.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Elliott and Way, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War, 28.

[14] Ibid.

[15] The size of the cornfield was estimated by one of the men from the 11th Wisconsin to be about 200 acres. Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: July 28, 1862 correspondence.

[16] ORA, 143.

[17] St. Louis Democrat, July 17, 1862.

[18] Ibid.

[19] The confusion here was probably the arrival of elements of the 15th Texas Cavalry, who indeed might have been game for an attck.. See, “The Confederate Defeat at Cache River,” The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LII, No. II, Summer 1993, 150.

[20] ORA, 146-149, 151.

[21] Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: July 16, 23, 1862, correspondences.

[22] Ibid.

[23] Letter from 11th Wisconsin to the Governor, July 10, 1862. Wisconsin Adjutant General’s Office: Records of Civil War Regiments, Correspondences, 1861-1865, box 56, folder 2.

[24] ORA, 148-151.

[25] The other companies from the 11th Wisconsin: I, H, and G.

[26] We do not know whether these men were some of the guerrillas Hindman called on, or if they were scouts or Texas Rangers.

[27] Henry P. Strong Papers, “Patriot War Correspondence,” July 23, 1862 of the 11th Wisconsin.

[28] Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: July 28, 1862, correspondence by “The Chip;” Henry P. Strong “Patriot War Correspondence,” July 23, 1862.

[29] Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: July 16, 18, 1862 correspondences, one by Company D member, C. McCarthy, who was wounded during the engagement.

[30] Shea, 135; see footnote 28 for 11th Wisconsin soldier quote concerning Hovey’s order. See also Henry P. Strong Papers, “Patriot War Correspondence,” July 23, 1862.

[31] Henry Twining correspondence to Janesville Daily Gazette, July 25, 1862; Correspondence to the Wisconsin State Journal, “The War in Arkansas”, August 25, 1862.

[32] ORA, 143

[33] Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: July 16, 1862, McCarthy correspondence and July 28 correspondence by “The Chip,” and July 16 correspondence by “Ralph.”

[34] Ibid.; ORA, 147; Elliott and Way, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War, 28; Henry P. Strong correspondence to the Missouri Democrat, dated July 21, 1862, Henry P. Strong papers, WSHA.

[35] B. P. Gallaway, The Ragged Rebel: A Common Soldier in W.H. Parson’s Texas Cavalry (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1988), 46-47.

[36] Nelson and Squier, “The Confederate Defense of Northeast Arkansas and the Battle of Cotton Plant, Arkansas, July 7, 1862,” Woodruff County (Ark.) Historical Society publication, Rivers & Roads & Points in Between 16 (Spring, 1989), 14.

[37] This is also confirmed by the 33rd Illinois, Elliott and Way, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War, 28. See also, Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4: July 23, 1862 correspondent from “Monterey.”

[38] St. Louis Daily Democrat, July 17, 1862; Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July, 1862.

[39] Gallaway, The Ragged Rebel: A Common Soldier in W.H. Parson’s Texas Cavalry, 46-47; Nelson and Squier, 14; ORA, 143-144; Shea, 138-139,148

[40] Two to three shots per minute would be the exception, especially when under fire.

[41] Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: Correspondences by “Monterey,” “The Chip;” and “Ralph;” Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July, 1862;

[42] Quiner Papers, Correspondences by “Monterey,” which is one of Strong’s pseudonyms.

[43] Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July, 1862; Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: Correspondences by “Monterey,” “The Chip;” and “Ralph.”

[44] Elliott and Way, History of the Thirty-Third Regiment Illinois Veteran Volunteer Infantry of the Civil War, 28, 131.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July, 1862;

[47] Ibid.; ORA, 144; Quiner Papers, Reel 1, Vol. 4 and Reel 2, Vol. 5: Correspondences by “Monterey;” Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July, 1862.

[48] Quiner Papers, Correspondences by C McCarthy, July 18, 1862; Elliott and Way, 28; Nelson and Squier, 17.

[49] ORA,144.

[50] Correspondence to “The Republican,” Henry P. Strong Letters, July 1862.

[51] Shea 146-147.

]]>John A. Burnham, who was a member of the 33rd Illinois from Normal, provides an interesting account of the Battle of Bayou Cache, also known as “Cotton Plant.” As most of you know, I have written extensively on this battle in both my book, and an article that I have submitted to the Arkansas Historical Quarterly. This particular account popped up just recently on google books.

If you wish to see the background info on the fight, please refer to the above links:

The Normal regiment found itself at Pilot Knob, Mo., September 20, 1861. Here and near here its officers and soldiers were taught many of the important first lessons in soldiery and military tactics.

Although the Normal contingent formed the nucleus of the 33rd regiment, yet it contained more than nine hundred other members who sometimes felt the Normalites were a little too much inclined to over-rate themselves, and considerable jealousy was early aroused, disappearing, however, as soon as

it was seen that we were always ready to prove by acts and not by words that we were in the war for the good of the cause, and not to promote our own selfish interests. It was not long before we were proud of our comrades, and our comrades were proud to be associated with those who had originated the idea of the schoolmaster’s regiment.Its first baptism of fire was at Fredericktown, Mo., October 21, 1861, just enough like war to give us a slight zest for more, not a man killed, not a drop of the Regiment’s blood spilled, and the victory was important.

In camp at Ironton, Mo., during the winter of 1861 and 1862, our regiment suffered from sickness but gradually improved itself in military drill, and perfected itself in hard marching during the following spring and summer.

Colonel Hovey won his promotion on this march, which is the main reason for the insertion of a brief account of the battle of Bayou Cache, July 7, 1862.

Our regiment formed a part of the advance guard of General Curtis’ army of 15,000 men, marching thru Missouri and Arkansas on the way to Little Rock. The Rebels, for several days, obstructed our march by felling trees in the roads and in other ways, without giving us fight. On the morning of July 7, four companies of the 33rd regiment, with as many more from the 11th Wisconsin regiment, were reconnoitering in advance, removing the blockades, when we fell into an ambush of Texan rangers.We were driven back at first with severe loss, although not until Company A in charge of a smallcannon belonging to an Indiana battery had resisted a savage attempt to capture the gun. First Sergeant Edward M. Pike, a Normal student now living at Chenoa, Ill., aided by one other man, coupled the cannon by main strength to its foremost wheels, barely saving it from capture, just as the rebels were on the point of reaching for the artillery horses’ bridles. He received a bullet through his cap and for his muscular activity, daring and bravery, was a few years ago given, by the Secretary of War, a medal of honor, which is the only medal granted to a member of the 33rd regiment, to my knowledge. Captain Potter, in command of our company, was severely wounded, with several others. Just as we started to the rear he gave me the command of the company and told me to take it back to the rear. As a matter of fact the company or something else was taking me rapidly back to the rear without orders, and I shall never forget my satisfaction at being under orders to do what was so remarkably agreeable as was that retreat, and feeling that of all that rushing throng pushing our way to the rear amidst the crashing bullets and falling branches, I was perhaps the only one fortunate enough to be

acting under orders.Colonel Hovey was in the rear with the main army, but fortunately was mounted and on his way to join us when he heard the sound of battle and rode like the wind to our assistance. He met our retreating forces, about five hundred in all, and instantly attempted with great success to halt the troops at a good point for resistance. I shall never forget his courageous and desperate attempts to rally the troops. I was very near to his person when some rebel buckshot passed through his clothing and cut the skin of the upper part of his breast. The pain was intense as the first sensation was like being shot thru the lungs. He turned pale and staggered, and just as I was almost near enuf for assistance, I saw him tear open the clothing and feel of his wound. In an instant his countenance brightened as he drew forth his hand containing two or three

buckshot which had merely penetrated the skin. He said immediately, ” It is nothing but a flesh wound and some buckshot. I am not hurt,” and immediately proceeded more vigorously than before to arrange the disorganized soldiers for desperatedefense. The rally was successful, other troops arrived, the force of Texans was soon driven back and we were grandly

victorious.

His descriptions offers some detail that other reports did not provide, though he essentially, as has been the case, follows only the exploits of the 33rd Illinois Regiment at the expense of the 11th. Now, this, of course, is not unusual.

]]>Arkansas, July 7, 1862, near Hill’s Plantation and Cache River a small battle took place. On the afternoon of July 6, 1862, Maj. Gen. Samuel R. Curtis’ Army of the Southwest was strung out along Clarendon Road when it was discovered that the Confederates had fallen enough trees in front of James’s Ferry to halt their advance. At that point, where the swampy bayou and cypress trees choked the road, it would be impossible to circumvent the obstacle; they would have to cut their way through the barricade. This meant they were there for the night. There was a brief skirmish between the 3rd Iowa Cavalry and about fifteen or so Confederate irregulars. In command of the advanced division was Brig. Gen. Frederick Steele. That night scouts were sent across the river to the other side of James’s Ferry while work on the blockade commenced.

The next morning Curtis instructed Steele to send out a reconnaissance while a bridgehead was established as they finished up clearing the road. While the Army of the Southwest floundered on Clarendon Road, Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas C. Hindman was hurriedly trying to get his ragtag group of Texas (Rangers) and Arkansas troops to Cache River in time to strike Curtis’ army while it was still bogged down.

At about 6:00 a.m., on the 7th, Colonel Charles E. Hovey, in command of Second Brigade, was ordered by Steele to take his men and form the bridgehead as well send out part of his force in reconnaissance. Once across Hovey sent Colonel Charles L. Harris of the 11th Wisconsin ahead with 8 companies (D,I, H, and G of the 11th Wisconsin and, A, E, I, and K of the 33rd Illinois) along with a small cannon. Harris led his men down Clarendon Road to a fork at the edge of a cornfield where Hill’s Plantation resided. Once there his men stopped for a short time as skirmishers headed down Des Arc Road (to the South) where they ran into a group of Confederates who fired a single volley and fled.

Long story short, for this introduction as I will get into more detail later, Harris would be instructed by Hovey to rapidly move down Des Arc Road in an attempt to “rescue a prisoner just captured” by the Confederates. At a turn in the road near a swamp, the four companies of the 11th Wisconsin ran smack into 2,000 Confederates and were nearly engulfed along the road.

According to official records, “[as] Union Col. C.L. Harris moved forward with elements of the 11th Wisconsin, 33rd Illinois, and the 1st Indiana Cavalry, he blundered into an ambuscade.” This is repeated countless times virtually wherever you find a description of the initial stages of the battle which was won by the Federals.

My mission was to investigate the battle and see if there might be some flaws contained within the accounts and documentation. Let’s briefly look at the documents involved. How about the Official Records, The War of the Rebellion: a Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies

There are only 6 reports concerning the fight. The first one is a short introduction by Curtis, who was miles away. The second one is from Steele, who also was not present. The third one, yup, Brig. Gen. William P. Benton who also was not there. The fourth was from Hovey, who was not present during the initial phases of the attack, and the fifth from Col. Conrad Baker, commanding Fourth Brigade, who was also not in attendance. The last one was from Lieu. Colonel William F. Wood, who was not present during the initial attack but came on later to play a crucial role.

Colonel Harris of the 11th Wisconsin either did not file a report or one did not survive. He was severely wounded and that may be the reason for a lack of representation on the part of 11th Wisconsin. Strangely, there were other officers in the 11th who were either not allowed to file a report or none survived, including Lieu. Colonel Charles A. Wood (not to be confused with Wood, 1st Indiana Cav.).

There are not many significant accounts of the battle that I could find. William L. Shea’s “The Confederate Defeat at Cache River,” published in The Arkansas Historical Quarterly, Vol. LII, No. 2, Summer 1993, represents the most modern account. Numerous books on the Civil War in Arkansas briefly mention the event, such as “Rugged and Sublime: The Civil War in Arkansas” (University of Arkansas Press, 1994), but as the chapter that covered this fight was by Shea, it did not different from his above article. Also, Glenn T. Nelson and John D. Squier, “The Confederate Defense of Northeast Arkansas and the Battle of Cotton Plant, Arkansas, July 7, 1862,” Woodruff County (Ark.) Historical Society, Rivers, Roads & Points in Between, (Spring, 1989). The battle has also been called “Cotton Plant,” “Round Hill,” and “Hill’s Plantation.”

Shea’s article essentially follows the narrative given by Hovey in his official report. Shea also cites Elloit and Way’s “History of the Thirty-Third Illinois Regiment…,” as well as a report by William Fayel, a Civil War journalist who Shea calls “unusually reliable.” And I do agree that journalist, as opposed to regiment correspondents, are far more objective. But the main problem here is that it appears Fayel was also not present during the fight. (Still investigating this.) So we have a bunch of reports from folks who were not even there. And on top of that, not all of them agree on what happened.

Shea’s cited sources seem slanted to the 33rd Illinois and this perhaps makes his research flawed. For example, he sites Elloit and Way’s regiment history 8 times while never citing the 11th Wisconsin Regimental history (granted it does not cover the battle in great detail). The lone representatives of the 11th Wisconsin in Shea’s research are: Edward B. Quiner’s “The Military History of Wisconsin” (Chicago, 1866), the memoirs of Calvin P. Alling who served in the company D but was not present during the fight, and a letter from J.C. (Shea incorrectly calls him “I.C.”) Metcalf of the 2nd Wisconsin Cavalry, which he cited from the Quiner Papers. The quality of the sources is important, and I understand that, however there are several good sources that represent the 11th Regiment’s point of view that Shea does not include.

Shea seems to largely ignore (for lack of better wording as I do not know) the dozen or so correspondences found in the Quiner Papers, along with several other accounts written by members of the 11th Regiment including one who was involved in the fight (McCarthy, Company D) and was wounded. Regimental correspondents and histories often forget to mention the acts of other regiments during battles and thus reliability is an issue. However, Shea has no problem citing ones that favored the 33rd Illinois Regiment, or at least that’s the impression. Also, he largely ignored the 1st Indiana Cavalry who played a crucial role in securing the victory. I have already request diaries and letters from Indiana archives. Shea comes to the conclusion that Hovey and the 33rd Illinois saved the day. He also contends that parts of the 11th Wisconsin fled the field. Additionally, there is some controversy centering on Wood and the 1st Indiana Cavalry who I feel deserve more respect than has been given to them. I feel Hovey’s exploits are over-rated and maybe even false. All this I will get into later in more detail.

So I plunge forward and see if I can find enough evidence to redeem what appears to be a gross misrepresentation of Colonel Harris and the 11th Wisconsin Infantry Regiment. I will keep you informed, cheers!

]]>