[I did get some bad news, my publisher (McFarland) is not going to include my Prologue, which I understand their reasoning, but I also thought it was some good writing. So I have included it here as a teaser for the book:]

Prologue

He stood six feet three inches tall and weighed as much as two average-sized men put together. He was a giant, and by all accounts a “stout” man, so large his sword belt did not fit him. Brigadier General Michael K. Lawler was truly one of the most colorful and intriguing characters of the Civil War. He now commanded General Carr’s Second Brigade, replacing Colonel Stone. Secretary of War, Charles Dana, once said of Lawler, “He is as brave as a lion, and has as much brains.” For good or bad, the Eleventh Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment was now under Lawler’s command. A gruff Irishman with undeniable wit and charm, he was known for his simple adage, “If you see a head, hit it.” This probably summed up his entire understanding of military strategy. He was a man of fearless action, and little else.*

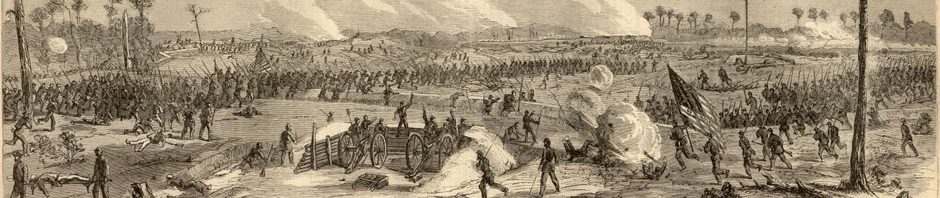

General Carr ordered Lawler’s brigade to move in on the extreme right, guarding the right flank of his division. Lawler sent Colonel Harris and the Eleventh Wisconsin regiment ahead through thick woods. Harris deployed Companies A and F as skirmishers. Suddenly cannon shots whistled overhead. The men momentarily ducked, but then went about their business. The rest of the brigade-the Twenty-first, Twenty-second, and Twenty-third Iowa regiments-moved out and followed the Eleventh Wisconsin as they made their way to a clearing just north of the opposing Rebel rifle pits, at the far end of a wide field. As Lawler reached the edge of the wooded area, on the right-most flank of Carr’s division, he found himself facing a deep field bordered by a swampy lowland, nestled in front of an entrenched enemy line. Although hunkered down behind makeshift cotton bales and logs, there were still plenty of heads to hit, with enemy lines continuing a mile or so to his left and out of sight. To his right was the river, which could not be waded.

By late afternoon all four regiments were strung out along the tree line, with skirmishers posted at the edge of the clearing. Sharpshooters engaged their butternut counterparts with sporadic fire but few results. As the afternoon progressed, the sun and humidity-choked air made the men uncomfortable. At about 3 o’clock Lawler walked his line and conferred with his subordinates, impatiently waiting on what he hoped would be an order to attack the enemy. The men sweated profusely in the hot, sticky air, dodging enemy gunfire and occasionally returning it in kind.

Lawler peeled off his sweat-drenched jacket and flung it down in frustration. He stood for a moment in his un-tucked checkered shirt and double-seated cavalryman’s breeches. His iron scabbard and sword flung over his shoulder and “dangling from his side” as he took a few steps the spurs on his heels jingled. He unbuttoned his collar and peered across the field at the Rebel line, seemingly taunting him to come at them.

His line continued to return fire sporadically, but it served only to waste ammunition. Taunts of “You missed me Billy Yank!” and “I’ll get you Johnny Reb!” rang across the field. They were just wasting time. Lawler’s frustration continued to grow. But at last a scout informed him that a floodplain depression in the field might allow his men to approach the enemy with some cover. With this new piece of information, and sensing Lawler’s frustration, Colonel Kinsman of the Twenty-third Iowa approached and proposed that his regiment fix bayonets and charge the enemy. Lawler readily agreed, but instead of one regiment, he decided to send his whole brigade. He was tired of waiting around.

A small battery of guns from the First Wisconsin deployed at the edge of another clearing would provide some covering fire for the assault. They also had additional support from two regiments of Indiana troops. Realizing that he needed some kind of diversion to draw attention away from his real point of attack, Lawler ordered two companies of Hoosiers to advance as skirmishers in hopes of distracting the Rebels.

Colonel Harris moved down his line, telling his “brave lads” to cast off their knapsacks and blankets, and to “fix bayonets” in preparation for the charge. Sergeant Samuel Kirkpatrick passed the order along to his Farmers Guards as word spread that a “bloody battle was anticipated.” Hearing that they were to charge, Henry Twining and the rest of Company C quickly removed their knapsacks and fastened their bayonets. Drenched in sweat they removed their sweat wool jackets in order to lighten their load. Brothers Oliver and Jesse Mather stood side-by-side, as usual, looking nervously across the field and to the swamp below. A line of rifle pits with hundreds-thousands-of Rebel soldiers just itching to get a shot at them was all they could see. Stray bullets continued to whiz by as Lawler’s troops formed their battle line.

For the most part, it would be a surprise attack. Most of Lawler’s men would emerge from the woods and rush across the wide field, taking fire most of the way. Each regiment was staggered along the tree line, the farther down the greater the distance to travel. For the Eleventh Wisconsin, second from the end, their initial starting point was 500 yards away. Luckily they would get to move closer (several hundred yards) before charging. It was discovered that there was a gap between two adjacent rifle pits. This presented an opportunity if they acted swiftly. Using the floodplain, they would charge obliquely across the field taking fire from two sides (right and front) in an attempt to enter the end of the rifle pit below the swamp. There the men would have to wade through the muddy swamp, with rifles raised to their shoulders, then climb the small embankment and attack the rifle pits, taking direct fire from the enemy all the while.

Lawler inspected his men, giving nods of approval. Just a few days before, during the battle at Champion Hill, the general was brusque when a stray bullet caused one young soldier next to him to duck. “Don’t dodge!” he said. “Don’t you know when you hear the bullets they have already passed!” Lawler unsheathed his sword, holding it by his side, nostrils flaring as he took several deep breaths. About this time, Samuel Kirkpatrick noticed a rider galloping up to his position. Captain Whittlesey had been acting as division quartermaster when he heard the Eleventh Wisconsin was once again on the frontline. He found a horse and dashed off in hopes of making it in time. “Here he came in a lope on his horse,” said Samuel, “and took his place in front of our Co. and said ‘Come on boys, follow me.'” Just then the artillery opened up with spirited fire to aid their advance.

The companies that were to lead the charge were formed “with bayonets fixed” and the order was given to “charge!” Colonel Kinsman and his fierce regiment of Hawkeyes led the way, bursting out of the woods yelling and screaming as they charged across the field in what one reporter who witnessed the event later called “the most perilous and ludicrous” act he had ever witnessed.

About this time, General Grant received an urgent message via courier that he mistook as being from Halleck. This confused communication seemed to ask that he withdraw and return to Grand Gulf to support General Nathaniel Banks’s movement south of him.¨ He handed the message back with a quizzical grimace, when in the distance he heard cheering and the sounds of cannon fire coming from Lawler’s position, followed by the crackling of gunfire. Something was happening. “See that charge!” Grant told the courier, “I think it is too late to abandon this campaign.” And with that he galloped off toward the fighting.

All along the line, dumfounded Federal troops watched as Lawler’s crazed hoard of bluecoats emerged from the woods and dashed across the field to their certain destruction. Had an order been given to charge? What were they doing? Men looked around nervously, wondering if they too should charge. Not far down the line, the colonel of the Ninety-ninth Illinois regiment perched in the hot sun along his tree line, sweating it out in frustration, just as Lawler had. But he stood and cheered in delirious admiration as the wave of blue descended from the woods. Then, turning to his men with sword drawn, he shouted, “Boys, it’s getting too damned hot here. Let’s go for the cussed Rebels!” Regiments here and there began to emerge from the woods, charging straight at the Confederates. This was going to be a slaughter.

It was May 17th, 1863, twelve miles east of Vicksburg near the Big Black River. Across the field, the Eleventh Wisconsin Volunteer Regiment charged through smoke, exploding cannon fire and gunfire, barreling towards an entrenched enemy just waiting for them to come into range. They were a band of brothers who less than 24 months before were working on family farms, in sawmills and mines, as blacksmiths and gunsmiths, teachers and clerks. For the past 18 months they had traveled thousands of miles, seen sights they’d only dreamed of, experienced things they hoped to forget. And now they were about to participate in the most brutal kind of warfare, during the siege of Vicksburg.